William Atkinson, Violin Maker

The life and work of the Great British violin maker and historical neighbour.

On having a cello come in to the workshop for a new bridge and spruce up, I was delighted to see that it was made by none other than the illustrious William Atkinson, a great instrument maker of his day, once resident of close by Tottenham, north London.

Whilst taking the time to make a bridge befitting of this beautiful, powerful cello, I saw in his work a supremely confident and strong style. Using high quality materials and the abilities of an extremely talented craftsman, he had created a cello of great character and depth.

Above: the soundholes of the cello, with Atkinson’s stamp below the button on the back.

Below: details of the long, curved beestings of the purfling and deep red varnish of the front.

Made in Tottenham in 1908, the cello is a very fine example of an instrument of its day, with a deep, rich Edwardian varnish. Atkinson’s varnish was the subject of much discussion, the maker taking the recipe to his grave. His obituary, written in the Daily Express after his death in 1929 reads:

“The old man realised too late that he was dying, and tried to impart the secret to his son, but the effort was too much for him. He fell back on his pillow, dead….”

He also said of his own varnish during an interview with the Southend Standard, 1928:

“If I were asked what was my greatest gift, I should say it was to make a violin, but I would not spend five minutes on it if I had not got the varnish I use. That varnish is my own, and I would stake my life it is the same varnish the old masters used.”

Above: The confidently carved, stylish scroll of the cello

Below: The original copperplate label inside the cello

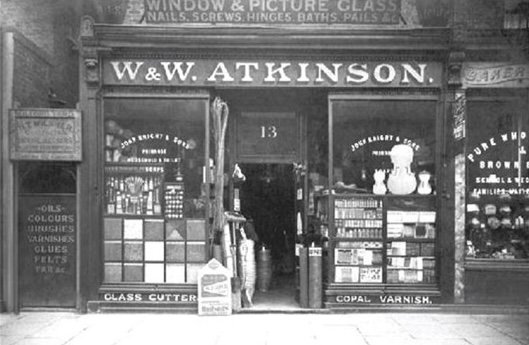

Reading the label, I was inspired to find the original location of his workshop in nearby Tottenham. After doing some research and finding the address of where his workshop was, I jumped on my motorbike and headed 3 miles east from Crouch End to 13 Church Road to find it.

Above: The original shop at 13 Church Road c. 1880 - 1911.

Below: The shop’s location today, in 2022.

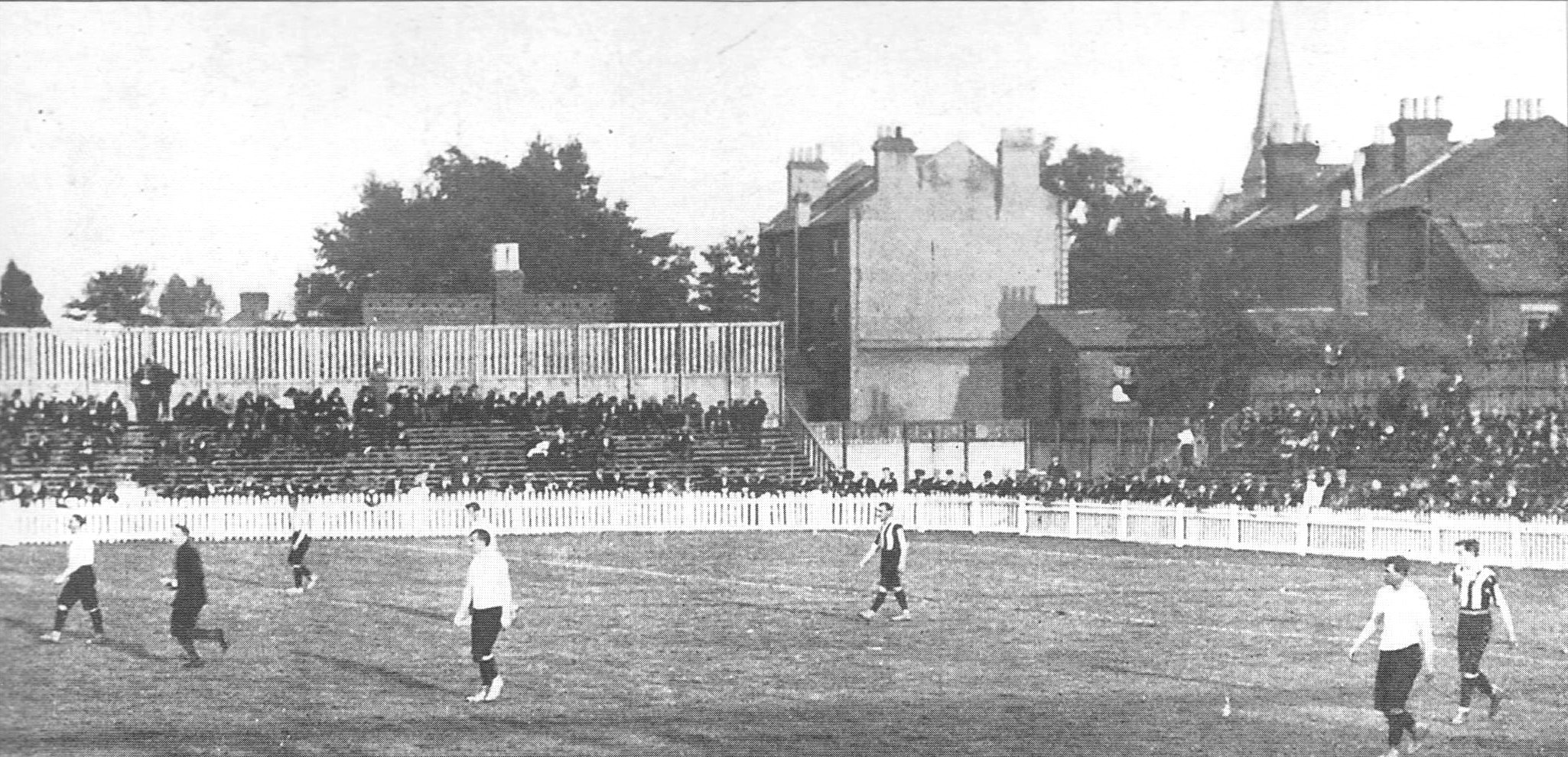

The block has now been redeveloped and behind lies the enormous football stadium of north London team Tottenham Hotspur. The football club has been located here since 1899, William Atkinson being one of the craftsmen commissioned to construct its original grandstand.

Above: Tottenham Hotspur playing their first match at White Hart Lane in 1899, the grandstand of which was constructed in part by Atkinson, who’s shop was just across the road.

Below: The new Tottenham Hotspur stadium today, completed in 2019

Biography of the maker

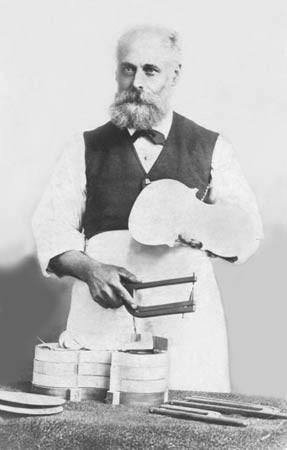

Born in Stepney, east London in 1851, William Thomas Reed Atkinson attended school until he was 14. He always maintained that he made his early acoustical and varnishes experiments at school. At 14 he was packed off to Birkenhead to work in his uncle's pub. He did not last long there, and soon joined the Merchant Navy and served as a 2nd steward on steamships working out of Liverpool. His granddaughter says that on one occasion Atkinson’s ship took in tow the encased and floating Cleopatra’s Needle, now standing on the Thames embankment at Westminster, which had broken away in a storm from a ship chartered to bring it to London.

By 1869, he was back in London with his parents and had become apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner. He worked for Tottenham builder Arthur Porter (his future brother-in-law) and amongst other things helped construct the original wooden grandstand at White Hart Lane. Atkinson suffered a serious injury during his time as a carpenter which led to him having a leg amputated below the knee and having to wear a wooden prosthesis.

Perhaps as a result of this accident, Atkinson began to concentrate on cabinet making. He took a great interest in wood finishes and varnishes, and experimented with his own compounds. When he took on a double-fronted shop with a rear workshop in Church Road, Tottenham in the 1880s, violin-making became the focus of his activities.

The shop, which was a general hardware and drysalters store, sold, as his granddaughter remarks, “Most things from a pin to a pitchfork: oils, pigments and varnishes were a speciality”. The shop also displayed specimens of Atkinson’s work: violins, violas and cellos, which were fashioned in the workshop to the rear.

Above: Violin by William Atkinson, 1904

As the air was becoming increasingly sooty in London, Atkinson moved to the village of Paglesham, Essex in 1911 where he took over the village general stores and Post Office at Church End. The idea was for his wife to run the Post Office and general store; they could live in the accommodation over the shop whilst on the third floor there was a workshop where he could devote his time to violin making.

To assist in the process of drying the varnish on violins, he rigged up a “washing line” and pulley system out of the third floor workshop window to a tall post in the garden. On this line he would hang violins to dry and winch them in and out through the window as the weather conditions required. An elderly couple, who had lived in Paglesham all their lives, remembered seeing the violins hanging out to dry on this “washing line” device as they went to school.

Above: Violin by William Atkinson, 1928

Atkinson also became a churchwarden of St Peter’s Church in the village, and that was an important part of his life. He continued to combine violin making with running his modest business with the help of his wife. Presumably a significant amount of Atkinson’s time was actually taken in making, his family running the other side of the business.

This had great advantage in that he never felt economically pressured, he was able to take time to make instruments completely to his satisfaction and was ruthless in rejecting anything, which did not come up to scratch. Atkinson was also liable to strip off the varnish if it was not perfect. It is thought that he made about 300 instruments in the white, but only 250 (including four violas and nine cellos) are accounted for, the rest having probably been destroyed.

The obituary, in the Strad of February 1930 (p. 566) states that he had, in recent years, sought out and destroyed many examples of his early work, which did not reach his mature standard of excellence. Atkinson clearly continued to experiment with varnish for many years, but essentially the oil varnish was put on by between eighteen and twenty-four coats, each having to dry before the next coat was put on.

The natural colour goes from pale straw to deep red-brown. It was stated that there was no added colouring matter in the varnish and Atkinson thought that it was similar to the varnish used by Italian painters of oils. As with so many English makers of this period who experimented with oil varnish, the results are sometimes not entirely satisfactory. At least one instrument has been seen where there has been noticeable deterioration and craquelure. But, in most cases, it seems to have survived very well, although its soft texture means that it is easily rubbed off by vigorous or careless usage

The Strad Magazine article of November 1900:

“He works on two original models. The measurements of model No. 1 are as follows:

Length of body……………….. 13 15/16”

Width across upper bouts…… 6 5/8”

Width across middle bouts….. 4 3 /8”

Width across lower bouts……. 8 3/16”

Depth of ribs at bottom………. 1 1/4”

Depth of ribs at top…………… 1 3/32”

Length of sound holes………… 3 1/32”

Distance between sound holes at top.. 1 19/32”

Elevation from ½ to .………. 5/8”

The measurements of model No. 2 are the same, except that at the top, middle and bottom bouts, it is 3/32 inches (3mm) narrower .……

Mr Atkinson’s wood is excellent. The figure of his maple is, as a rule, of medium width. His pine, which is from Berne, is simply perfect, having a “reed” rather under medium width, perfectly straight and well defined. His outline is in the best Italian style. It is gracefulness incarnate. Avery strong expression, but a true one. As the form of the gazelle is to that of the ordinary antelope, so is the outline of Atkinson to that of the ordinary fiddle.

The scroll is a masterly conception and of Pheidian beauty…. The first turn parts suddenly from the boss, as in the best examples of Stradivari. The edges are softened down gently, with black lines to emphasise the extreme outline.

The button is nearly semi-circular, with toned-down edge, and in perfect keeping with the contour. The margin is one-fifth (inch) (5 mm) wide. The edges are strong and rounded; but the 'rounding' is not over-pronounced. The elevation of the edge above the purflle-bed is almost imperceptible. The margin and edges present a delicately refined appearance. In fact, everything about the Atkinson violins betokens aristocratic refinement. The purfling is one-sixteenth (inch) (1.6 mm) wide, the inner strip having a width which is slightly greater than that of the outer ones combined.

The varnish is beautiful, ranging in colour from pale straw to light ruby, and of the most delicate tints. On a specimen recently seen by me, and which had been examined and most flatteringly commented upon by the late Duke Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the varnish was straw coloured and of the richest and tenderest hue. It is perfectly transparent and elastic, and soft as velvet to the touch. It is laid on in very thin coats and dried in the open air. Sometimes as many as twenty coats are given, but the final thickness of varnish is scarcely more than one-sixty-fourth of an inch (0.4mm).

Mr Atkinson’s tone is quite remarkable. It is not exactly like the tone of any other maker, classical or post classical, that I am acquainted with. The size of the instrument would lead one to expect a tone of small volume, but such is not the case. The tone is strong without being loud, penetrating without being piercing. One need not go to Atkinson for mere loudness. His is a mellow tone with a silver ring. Its echo in a large hall is like an anvil struck at a distant smithy and borne by the breeze. It is the tone of the dulcimer magnified, clarified, beatified. It is a delicious tone! For this reason the Atkinson fiddles are pre-eminently solo instruments. For the same reason it would not be wise to furnish the same orchestra with them throughout. That the gods rain honey on flowers is a kind provision; if they did it on grass they would spoil the world.’

Atkinson normally branded his instruments just below the button with his monogram. His label is written in the copperplate he undoubtedly learned at grammar school in Mile End Road, Stepney, and is varnished over to preserve it.

During his life the quality of his instruments was well recognised, and in his earlier years, he won a bronze medal in Paris in 1889 and a silver medal at Edinburgh in 1890.

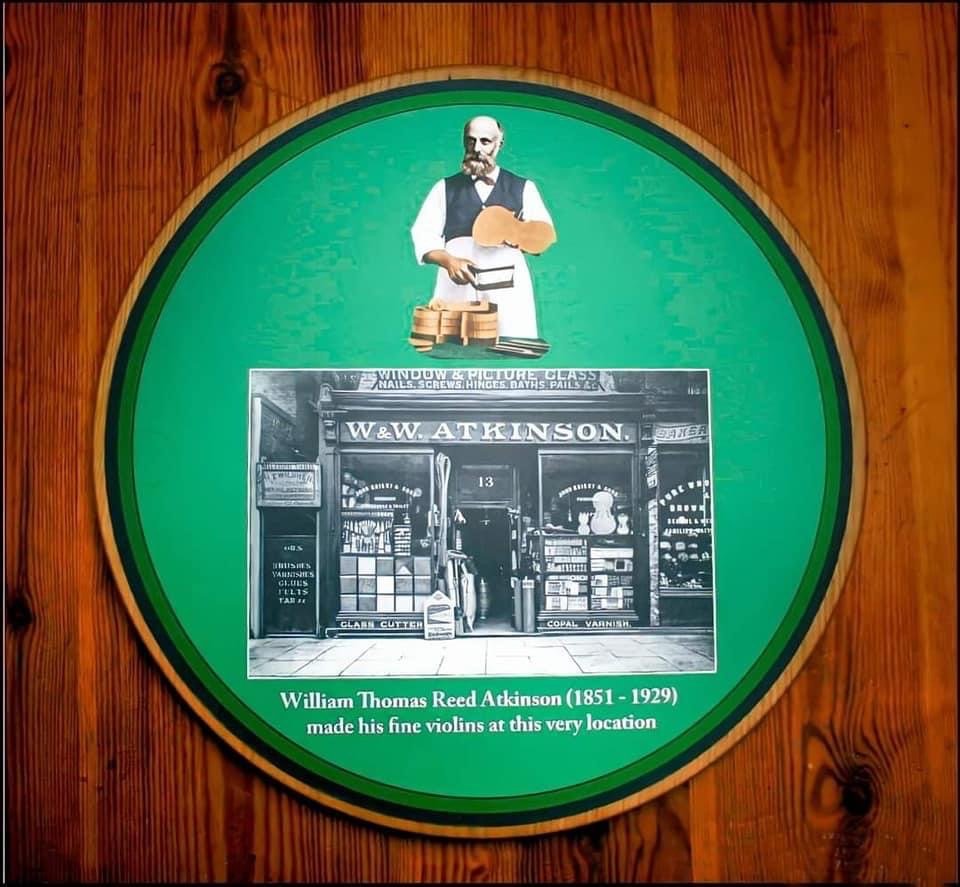

Above: The plaque at the location of Atkinson’s Church road shop, unveiled August 2021

Below: Tottenham cake baked for the occasion